Table of Contents

Prologue

PART I

Chapter One: The People’s Republic of Berkeley

Chapter Two: “I would rather be a superb meteor”

PART II

Chapter Three: They wore to war what they wore to church

Chapter Four: Steal this Book

Chapter Five: The Way We Were

Chapter Six: Stray Cat

Chapter Seven: The Bower of Bliss

PART III

Chapter Eight: ‘You do not have to walk on your knees’

Chapter Nine: Forever Young

CHAPTER 3:

They wore to war what they wore to church (excerpt)

The spring before I started kindergarten, Martin Luther King was murdered. I saw grainy images of King on tv wearing his white shirt and black suit. They wore to war what they wore to church, wrote Wesley Morris in the New York Times. I knew that King was a preacher who was killed for his beliefs, but didn’t understand it was about race, just that he was someone trying to do good, but the bad people killed him.

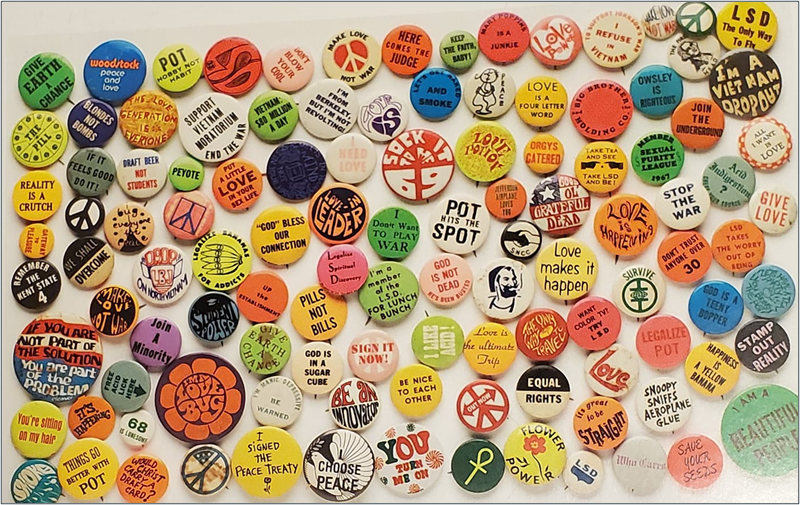

When King was shot, many Berkeley conservatives fled to the all white suburbs of Danville and Orinda as they saw Berkeley shifting further to the left. White flight and redlining (refusing housing loans in certain neighborhoods to black people), had been loopholes for white parents to avoid school integration, but Berkeley bussing was the retort. After World War two, black people were almost half the population in Berkeley, but like today the hills were almost all white and the flats primarily black. I didn’t know about the history of school integration which had been a failure after the first dramatic attempts where black children were escorted by federal marshals past crowds of spitting, hissing, rock throwing white parents. But Berkeley would try again. By decree, black kids would be bussed into white neighborhoods and white kids into black neighborhoods for their education from kindergarten through high school.

Since my fellow 5 year olds hadn’t been to school before, we didn’t know what this educational proclamation looked like. On my first day of school, I joined my neighborhood gang strolling past the barking dogs and collecting kids like a rolling ball of moss as we made our way up the hill towards Tilden Primary School. I was very excited to be starting school and felt safe in my group of kids that had been my community through the summer. I never paid attention to clothes before, but I had torn the pink polyester hem which I thought was satin, off my blanket and used it as a belt, feeling like it elevated my status to school kid.

The social experiment of enforced bussing was done with a lot of logistical planning, but no discussion with children to prepare them. No one spoke to us about the historical moment we were going through, that our education and our world were tilting; not our parents, not our teachers, and we never said a word to each other about what we were noticing.I saw the large yellow buses with placards naming them Green Duck or Blue Fish pulling up to the school and lines of kids running, twirling, skipping, dragging their feet and some even stubbornly remaining on the bus.

Our walk to school was a transition that made it easier to sit when the bell would ring. But the other kids had a more disparate energy. I knew the children arriving on buses were different from me; they seemed agitated after having a long ride to a new neighborhood.

Waiting for us in the classrooms was a new Afrocentric curriculum, making up for the erasure of black culture in education up to that point. The Third World Liberation Front made sure that black, Hispanic, Asian and indigenous voices sprouted up from under the concrete shaking the podium where white men made up the academic canon. Black Studies and Ethnic Studies now had a permanent place in academia for the first time since the founding of the University. And of course, this curriculum change trickled down to us. Heroes of black history --Rosa Parks, Jesse Owens, Harriet Tubman (excluding Malcolm X, he was saved for later) were posters on the walls. A white girl a few years older than me remembers the daily recitation of the lyric and title of James Brown’s hit song Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m proud. We read A Dream Deferred by Langston Hughes and many of my teachers were people of color. Louis Armstrong blew his horn, and we sang slave songs jump down, turn around, pick a bail of cotton instead of rounds of Row Row Row your Boat.

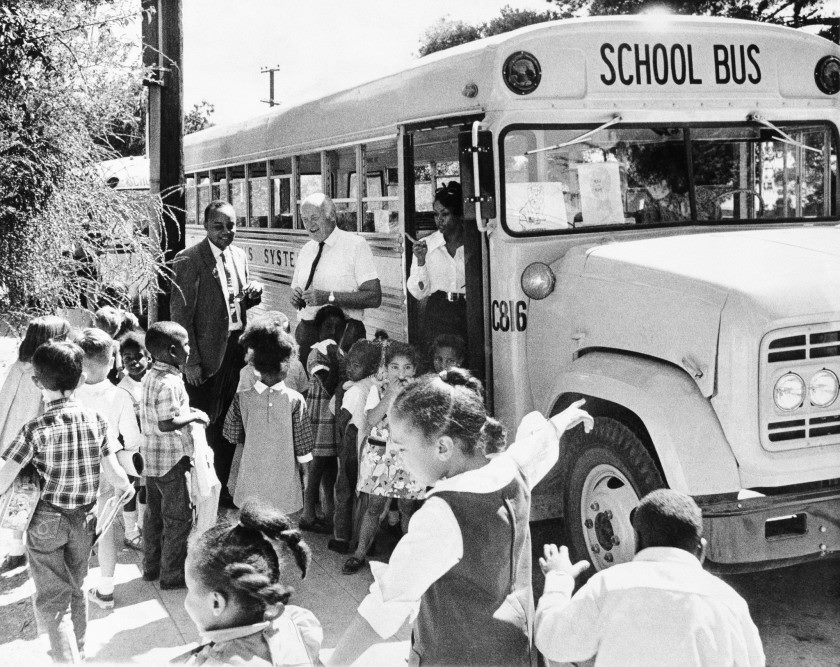

By 2nd grade, I learned about ‘the negroes’, sometimes referred to as blacks; I hadn’t connected them to breathing people. I studied a sanitized version of slavery that had sketches of people in chains. We focused on the excitement of the underground railroad, but we didn’t see what happened to those who were caught. I even read a Caldecott award winning children’s book on Abraham Lincoln that showed him towering over a bunch of people cowering near his ankles while he protected them; he was freeing them from slavery. They were drawings, not photographs. Like other illustrations in my picture books which included mermaids, fairies and talking animals, books connected me to the imagination, not reality. But also, in the illustrations, all the black people looked the same, colored in by a black pen, their eyes big, lips thick and hair kinky. The black people around me had skin of all tones, hair with different styles and such a variety of faces, that I didn’t see them as one. Just as a child has to connect the drawing of an apple in an ABC book to an actual apple, I hadn’t drawn that line. But mostly, in my child’s brain, I didn’t really believe people could do that, own other people.